Trenton, December 26, 1776

As found in the book, "The Hessians The Revolution", By Edward J. Lowell.

CHAPTER VIII.

TRENTON, DECEMBER 26, 1776.

After the capture of Fort Washington Sir William Howe showed unusual activity. The fort had fallen on the i6th of November, 1776, and on the 20th the British army crossed the Hudson into New Jersey. Fort Lee had become at once useless and incapable of defence. It was hastily evacuated, and artillery, tents, and provisions were abandoned with it. More than two thousand men, under General Greene, who had formed its garrison, barely escaped across the Hackensack, leaving seventy-three sick behind them. The condition of Washington’s army was desperate. The term of service of many of the militia-men expired on the 30th of November. These could by no means be induced to re-enlist, even for a short time, nor would the New Jersey militia turn out to protect their own state, a brigade of them disbanding on the day the British entered New Brunswick. Washington had left a detachment under Lee on the east side of the Hudson, and Lee now disregarded Washington’s repeated orders to join him, and grumbled instead of acting. About twenty-four hundred men under Lord Stirling were detached for the protection of Northern New Jersey, and four days afterwards ordered to defend the upper line of the Delaware; and the commander-inchief had at one time less than thirty-five hundred men with him. The march of the British across New Jersey was hardly opposed, though Washington retreated slowly before them, destroying the bridges. On the 8th of December he retired across the Delaware, removing all the boats for seventy miles to his own side of the river. There was a panic in Philadelphia, and Congress adjourned to Baltimore. Washington felt himself unable, with his small force, to prevent the passage of the British over the river.[Footnote: See Washington’s writings at the time, passim, and especially December I2th.—Washington Writings, vol. iv.p. 211.] Howe was not the man, however, to pursue a winter campaign with vigor. He returned to New York, leaving Cornwallis, and afterwards Grant, in command in New Jersey. Bancroft tells us that the state was given over to plunder and outrage, and that all attempts to restrain the Hessians were abandoned, under the apology that the habit of plunder prevented desertions. “They were led to believe,” quotes he, from the official report of a British officer, “ before they left Hesse-Cassel, that they were to come to America to establish their private fortunes, and hitherto they have certainly acted with that principle.”[Footnote: Bancroft, vol. ix. p. 216.] Washington, on the other hand, writes, on the 5th of February, 1777: “One thing I must remark in favor of the Hessians, and that is, that ür people who have been prisoners generally agree that they received much kinder treatment from them than from the British officers and soldiers.”[Footnote: Washington, vol. iv. p. 309.]

It was the belief of Washington that active operations would speedily be resumed, and that the British would march on Philadelphia as soon as the Delaware should be frozen over. A letter intercepted a day or two before Christmas confirmed this opinion.[Footnote: Washington, vol. iv. p. 244: The idea of some such stroke as the surprise of Trenton is first mentioned by Washington on the 14th of December. In a letter to Governor Trumbull he says that the troops who are coming from the north, with his present force, and that under General Lee, may enable him “to attempt a stroke upon the forces of the enemy, who lie a good deal scattered, and to all appearance in a state of security. A lucky blow in this quarter would be fatal to them, and would most certainly rouse the spirits of the people, which are quite sunk by our late misfortunes.”—Washington, vol. iv. p.220.] It became of the utmost importance to strike a blow before the enemy should be ready to move, and before the last day of December, when the term of service of many of his men would expire.

The disposition of troops made by General Grant, the British commander in New Jersey, was as follows: Princeton and New Brunswick were held by English’ detachments. Von Donop, commanding the Hessian grenadiers and the Forty-second Highianders, was at Bordentown. Rail, with the brigade which had been for some time under his orders, fifty Hessian chasseurs, twenty English light dragoons, and six field-pieces, was quartered at Trenton. Rail’s brigade was composed of three regiments of Hessians, which bore the names of Rail, von Knyphausen, and von Lossberg. It did not differ materially iii quality from other Hessian brigades. The regiment von Lossberg had especially distinguished itself at Chatterton Hill. Regiment Rail was made up of bad material, being one of those raised in a hurry to fill the tale of soldiers furnished by the Landgrave,[Footnote: Kapp’s “Soldatenhandel,” p.63.] but Cornwallis long afterwards told a committee of the House of Commons that Rail’s brigade, at Fort Washington, had won the admiration of the whole army.

The town of Trenton, then composed of about a hundred houses, lay on both sides of Assanpink Creek, near where that creek falls into the Delaware, the larger part of the town being on the western side of the creek. This was crossed by a bridge, over which the road led down the Delaware to Bordentown and Burlington. There were roads on both sides of the creek to Princeton. Of these, the one on the western side, passing through Maidenhead, was the shorter. There was also a road to Pennington, in a northwesterly direction, and two roads along the Delaware, going up stream, one near the bank and the other a mile or two from it. The last fell into the Pennington road a little way outside the town.

The regiments Rail and von Lossberg were quartered in the northern part of Trenton, the Knyphausen regiment in the southern part, on both sides of the bridge over the Assanpink. On this bridge a guard of twelve men was stationed. The soldiers in the town were scattered in the various houses, and in fine guns were stacked out of doors, in charge of two or three sentries. Pickets were thrown out on the roads west of the creek. The main guard was composed of an officer and seventy men.

Colonel Rall was a dashing officer of the old school. He was said to have asked to be quartered at Trenton, considering it the post of danger.[Footnote: MS. Journal of the Grenadier Battalion von Minnigerode.—Wieder. hold’s Diary.] He had done very well at Chatterton Hill, where the American right wing had been turned, and the fate of the day decided, by his brigade. He had taken a leading part in the storming of Fort Washington. The same adventurous spirit which in former years had led him to join the Russians under Orloff as a volunteer to fight against the Turks, served him on those occasions. The ease with which he had seen victories won, since he had come to America, had filled him with an overweening confidence. The ragged wretches who had been driven across New Jersey might capture a patrol or drive in a picket, but were, he thought, quite incapable of a serious attack on a Hessian brigade. “Earthworks 1” said he with an oath to Major von Dechow, who came to advise him to fortify the town; “only let them come on! We’ll meet them with the bayonet ;“ and when the same officer requested him to have some shoes sent from New York, he replied that that was all nonsense. He and his brigade would run barefoot over the ice to Philadelphia, and if the major did not want to share the honor, he might stay behind. General Grant, the English general commanding in New Jersey, shared Rail’s contempt for the rebels, and when the latter proposed to him to send a detachment to Maidenhead, to keep open the communication between Princeton and Trenton, replied scornfully that he could bridle the Jerseys with a corporal’s guard. Von Donop, who commanded at Bordentown, sent a captain of engineers to Trenton to induce Rail to allow the place to be fortified, but the latter was obstinate. Earthworks were unnecessary, he said. The rebels were good-for-nothing fellows. They had landed below the bridge several times already, and had been allowed to get away quietly, but now he (Rall) had taken measures. When they came again he would drive them back in good fashion. He hoped that Washington would come over, too, and then he could take him prisoner. So dangerous did Rail’s carelessness seem to his subordinates, that the officers of the Lossberg regiment sent off a letter of remonstrance to General von Heister, but too late.

Rall’s contempt for his enemy led him to neglect his most elementary duties. He seldom visited a post, he seldom consulted with an officer. He refused to name a place of safety for the baggage in case of an attack. “Nonsense,” said he, when asked to do so, “the rebels will not beat us.” Yet the men were constantly fatigued with unnecessary guard duty and countermarching. On the 22d of December, two dragoons, who had been sent to Princeton with a letter, were fired on in a wood. One of them was killed, the other rode back to Trenton and reported the attack. Rail, thereupon, sent three officers and one hundred men, with a cannon, to carry his letter, much to the amusement of the English. The detachment had to sleep on the ground, in bad weather, and march back the next morning. A sergeant and fifteen men would have been amply sufficient for the service.

On the 24th of December, 1776, a reconnoissance was sent out in the direction of Pennington, but was recalled after a march of a few miles. Towards dusk on the 25th an attack was made on the pickets north of the town, by a small reconnoitring party of Americans. The enemy were repulsed, with a loss to the Germans of six men wounded. A patrol of thirty men, under an ensign, was sent one or two miles in pursuit of the retreating Americans, but failed to come up with them. The picket at the junction of the upper river road and the Pennington road was then strengthened by about ten men, under Lieutenant Wiederhold, making it up to a total strength of twenty-five men. Rall made up his mind that all danger was over. He had lately been warned that an attack was imminent, and he took it for granted that the skirmish in which the pickets had been engaged was the attack of which he had been warned. Leslie, who commanded at Princeton, had sent word that Washington was preparing to cross the Delaware, but Rall gave no serious heed. He only ordered his own regiment, which was “of the day,” to stay in its quarters. There was, indeed, ground for his feeling of security. It was known to him that no large force of Americans was left in his part of Ne Jersey. Washington’s army lay beyond the Delaware, a ragged, half-armed mob of poor devils, who had lately beeii driven from state to state and from river to river. Great cakes of ice floated to and fro in the Delaware, drifting with the tide, and making all crossing dangerous. The night was boisterous, even for December, and before morning sleet and snow were driving through the streets. But within all was bright and cheerful. It was Christmas evening. The Germans, comfortably housed in Trenton, could laugh at the storm, and sleep securely.[Footnote: It has frequently been said that Washington surprised the Hessians, still sleepy from the festivities of Christmas. In Germany it is always Christmas Eve that is celebrated, and the Hessians would, therefore, have had thirty-six hours to recover from the effects of their potations before eight o’clock on the morning of the 26th. Rail, himself, is said to have been a drinker.]

Far differently was the night passed by the American army. The troops under the immediate command of Washington, at his camp on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware, above Trenton, numbered only twenty-four hundred men in condition to undertake an arduous expedition.[Footnote: Bancroft, vol. ix. p. 230. “About twenty-five hundred men.”—Diary of Captain Moses Brown of Glover’s regiment, kindly communicated by Edward 1. Browne, Esq.] These started at three o’clock on the afternoon of Christmas Day, every man carrying three days’ rations and forty rounds. They had with them eighteen field-pieces. This force reached MacKonkey’s Ferry at twilight. Here the boats were manned by Glover’s sailors, from Marblehead, and between the cakes of floating ice the little army was rowed across the river. So pitiful was their condition that a messenger who had followed them had easily traced their route “by the blood on the snow, from the feet of the men who wore broken shoes.”

Meanwhile, Cadwalader was to have crossed the river at Dunk’s Ferry, below Trenton, but the ice was packed against the Jersey shore, and, though men on foot could get over, there was no hope for artillery. The eighteen hundred men destined for this part of the expedition waited in vain through the December night. At four in the morning, Cadwalader, sure that Washington, like himself, had been turned back by the difficulties of the expedition, ordered his half-frozen men back to their freezing camp.[Footnote: Cadwalader to Washington, Sparks’s “ Correspondence,” vol. i. p. 309.] “The night,” writes

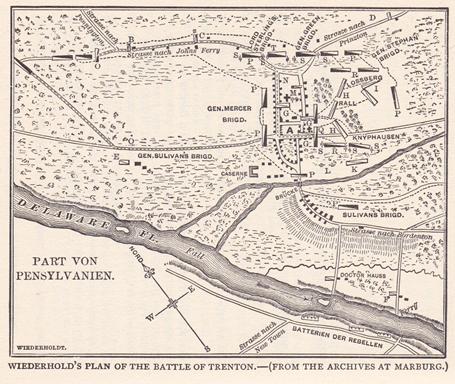

PLAN

of the affair which took place on the 26th of December, 1776, at Trenton, between a corps of six thousand rebels, commanded by General Washington, and a brigade of Hessians, commanded by Colonel Rail.

A. Trenton.

B. Picket of an officer and twenty-four men. (Wiederhold.)

C. Captain Altenbocum’s company of the Lossberg regiment, which was quartered in the neighborhood, and which formed in front of the captain’s quarters, while the picket occupied the enemy.

D. Picket of one captain, one officer, and seventy-five men.

E. One officer and fifty Jägers, who immediately withdrew over the bridge. (Grothausen.)

F. Detachment of one ocer and thirty men, which joined Donop’s corps.

G. Place where the regiments stopped after leaving the town, and where Colonel Rail attempted to make an attack on the town with his own regiment and that of Lossberg, but was violently driven back to

I. and taken prisoner with the regiments; meanwhile the Regiment von Knyphausen should have covered the flank.

K. Place where the Regiment von Knyphausen had likewise to surrender, after trying to reach the bridge. The cannon of the Lossberg regiment were with the Knyphausen regiment, and unfortunately stuck in the marsh; and while they were being extricated the ano ment for gaining the bridge was lost, and the bridge strongly occupied by the enemy.

L Cannon of the Lossberg regiment.

M. Cannon of the Knyphausen regiment, which were not with the regiment during the affair.

N. Cannon of Rail’s regiment, dismounted in the beginning.

0. Attack of the enemy from the wood.

P. The enemy advance and surround the town.

Q. Two battalions of the enemy following the Knyphausen regiment.

R. Last manceuvre and attack upon the Knyphausen regiment.

S. Cannon of the rebels.

T. Place where General Washington posted himself and gave his orders.

Thomas Rodney, “was as severe a night as ever I saw.” The river was so difficult to cross and so full of ice that it was four o’clock on the morning of the 26th of December before the troops and artillery were all got over and ready to march. They had still nine miles to go before reaching Trenton, and the storm had set in with fearful violence. The shivering soldiers climbed a steep hill and descended into the road, where the trees of the forest might give them a little shelter against the northeasterly storm. At Birmingham the army was divided into two columns. The right, under Sullivan, marched near the river, the left, under Washington, by the upper road. After a while, Sullivan sent word to Washington by one of his aides that the powder of his party was wet. “Then tell your general,” answered Washington, “to use the bayonet and penetrate into the town, for the town must be taken, and I am resolved to take it.” It was about an hour after daylight, and Lieutenant Wiederhold had drawn in his outer pickets. It had been a severe night with snow and sleet, but the enemy had not been seen. The little command huddled into a hut that served as a guard-house. Wiederhold happened to step to the door and look out. Suddenly the Americans were before him. He called to arms, and shots were exchanged. “The outguards made but small opposition,” says Washington, “though, for their numbers, they behaved very well, keeping up a constant retreating fire from behind houses. We presently saw their main body formed; [Footnote: This was John Cadwalader, brother to Lambert Cadwalader of the Continental service.—Washington, voL iv. p. 245, n.] but, from their motions, they seemed undetermined how to act.” Drums and bugles sounded in the streets of Trenton. Rail was still in bed, and sleepy in his cups. Lieutenant Biel, acting as Brigade Adjutant, was at first “ afraid” to rouse him,[Footnote: “Scheut sich” (Marburg Archives).] but hastened off to the main guard and despatched another lieutenant and forty men to support the pickets. As he returned to headquarters Rail was hanging out of the window in his night-shirt and crying,” What’s the matter?” The adjutant, in reply, asked if he had not heard the firing. Rail said he would be down at once, and presently he was dressed and at the door. A company of the Lossberg regiment, which had quarters on the Pennington road, and acted as an advanced guard, had formed across that road, and received the flying pickets, but had presently fallen back into the town. Washington was pressing in by King and Queen Streets (now Warren and Greene Streets), and Sullivan by the river road into Second Street. A part of Rail’s regiment presently succeeded in forming, and after a while Rail himself appeared, on horseback. Lieutenant Wiederhoid reported to him, saying that the enemy was in force, and not only above the town but also upon the right and the left. Rail asked how strong the enemy was. Wiederhold answered that he could not say, but that he had seen four or five battalions come out of the woods and that three of them had fired at him before he fell back. Rail called out to advance, but seemed dazed, and unable to form a plan. His forces were still in disorder. Rail struck off to the right into an apple orchard east of the town, and tried to obtain command of the Princeton road. He was turned back by Hand’s Pennsylvania regiment. He then determined to force his way into the town again with his own and the Lossberg regiments; at least, with as much of them as had been brought together. This he is said to have attempted in order to bring off his baggage, and the plunder of the preceding weeks. He was received, however, by a shower of lead from windows and doorways and from behind trees and wails. The Hessian ammunition was wet by the driving storm. The Americans charged again, and the Hessians were driven farther than they had come. Rall was mortally wounded by a bullet, and the two German regiments, thrown into confusion, laid down their arms.

The Knyphausen regiment fared little better. When Rail left the orchard and turned again towards Trenton, Major von Dechow determined to fight his way back over the Assanpink bridge and strike for Bordentown, where lay Donop’s force. It was impossible to accomplish this, for Sullivan had already occupied the bridge. Two cannons stuck fast in a piece of boggy ground, and time was lost in trying to extricate them. Dechow was wounded. A few of the soldiers succeeded in fording the stream, but by far the greater number were surrounded and surrendered to Lord Stirling, reserving their private baggage and the swords of the officers. Those who escaped made their way to Princeton. The chasseurs and English dragoons also escaped and reached Bordentown. Lieutenant Grothausen of the chasseurs was accused of running away too soon. He had been posted with fifty men on the lower river road, and on Sullivan’s approach he retreated before him over the Assanp ink bridge. According to Bancroft, the whole number who thus got off was one hundred and sixty-two. Washington, in his first report to Congress, gives the number of those who surrendered at twenty-three officers and eight hundred and eighty-six men. A few more afterwards found in Trenton raised this number to about one thousand. “Colonel Rahl [sic], the commanding officer, and seven others,” he writes, “were found wounded in the town. I do not exactly know how many were killed; but I fancy not above twenty or thirty; as they never made any regular stand. Our loss is very trifling indeed, only two officers and one or two privates wounded.” [Footnote: Washington, vol. iv. p. 247. Bancroft gives the numbers as seventeen Hessians killed and seventy-eight wounded.]

Washington’s force being inferior in numbers to that of the English and Hessians to the south of him, and a strong battalion of light infantry being at Princeton, he thought it prudent to retire across the Delaware the same evening with the prisoners and artillery he had taken.

The news of the victory of the Americans was received in New York with grief and indignation. Old Heister, already out of favor with Sir William Howe, may have seen in it the omen of his own recall. He wrote on the 5th of January to the Landgrave’s minister, Schlieffen, announcing the event. According to his story, Rail’s brigade had been surprised by ten thousand men, and the disaster was caused by that colonel’s rashness in advancing to meet this superior force, instead of retiring at once behind the Assanpink. Heister acknowledges the loss of fifteen stands of colors.[Footnote: Quoted in Eelking’s “IIulfstruppen,” vol. i. pp. 375, 376.]

The Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel was very angry. He complained that such an event would have been impossible, had not all discipline been relaxed. He ordered an investigation to be made as soon as the officers, who were then prisoners in American hands, should have been exchanged, and threatened to hold those guilty of misconduct to the strictest responsibility. He declared that he would never restore colors to the regiments that had lost them until they should have taken an equal number from the enemy. He wrote to Knyphausen that he hoped that general, like himself, was filled with proper grief and shame; that it was necessary to wipe out the spot on his honor, and that Knyphausen must not rest until his troops had smothered the remembrance of this wretched affair in a crowd of famous deeds.[Footnote: Eelking’s “Hulfstruppen,” vol. 1. p. 377. A letter which has fre. quently been published, purporting to be written at this time by a Prince of Hesse-Cassel to a Baron Hohendorf, or Hogendorif, commanding Hessian troops in America, is a clumsy forgery.—Kapp’s “Soldatenhandel,” 2d ed. pp. I—2OI and 255.] The Landgrave was indiscriminate in his anger. The true offender against the rules of military duty died in Colonel Rall. It was the opinion of soldiers at the time, and has remained the opinion of those who have studied the matter since, that the defeat and capture of the Hessian brigade at Trenton might have been prevented by common military precautions on the part of its commander. Cornwallis afterwards told a committee of the House of Commons, that in Donop’s opinion Rall could have held out until Donop could have come to his relief from Bordentown, if he had obeyed Sir William Howe’s orders and erected red,ubts. These Rail was repeatedly urged to build by his subordinate officers. That those under his command should somewhat have participated in the relaxation of discipline wantonly encouraged by their commander was but natural. In the end they all fought bravely, many of them being wounded, though the loss of privates was but small. That an earlier retreat might have enabled the Hessians to escape is possible. But soldiers should not be heavily blamed for trying to hold their ground when surprised, nor is Rail’s error, if it were one, in trying to cut his way out towards Princeton, rather than towards Bordentown, to be laid to the score of his subordinates.[Footnote: The only dissenting voice is that of Ewald, who excuses Rail, and lays the blame on the officer of chasseurs (Grothausen) who should have discovered the enemy. Ewald also blames Donop for having been decoyed from Bordentown to Mount Holly, and out of supporting distance of Trenton, by false reports. Ewald, who was under Donop at the time, says, moreover, that this little affair of Trenton caused such a panic in the English army, hitherto regularly victorious since the opening of the campaign, that they continually thought they saw Washington and his soldiers, and did not get over their fear until they had fought again. Ewald’s “Belehrungen,” vol. ii. p. 127. Grant, Rail’s immediate superior, writes on December 27 “I did not think that all the rebels in America would have taken that brigade prisoners” (Archives at Marburg). The finding of the court-martial blamed Rail and Dechow, both dead (ibid.). For the battle of Trenton see authorities quoted and Eelking’s “Hulfstruppen,” vol. i. pp. 112, 132; (MSS.) Wiederhold’s Diary, journals of the regiment von Lossberg, and Grenadier Battalion von Minnigerode.]

The importance of Trenton to the Americans is not to be reckoned by the mere numerical test of killed, wounded, and prisoners. It was a new proof to the unskilled and destitute colonists that they were good for something as soldiers, and that their cause was not hopeless. Coming after a long course of retreat and disaster, it inspired them with fresh courage. Bunker Hill had taught the Americans that British regulars could be resisted. Trenton proved to them in an hour of despondency that the dreaded Hessians could be conquered.

[ The Hessians In The Revolution ]